9 October 2021 – 5 December 2021

Knowing

Odun Orimolade

How do we know?

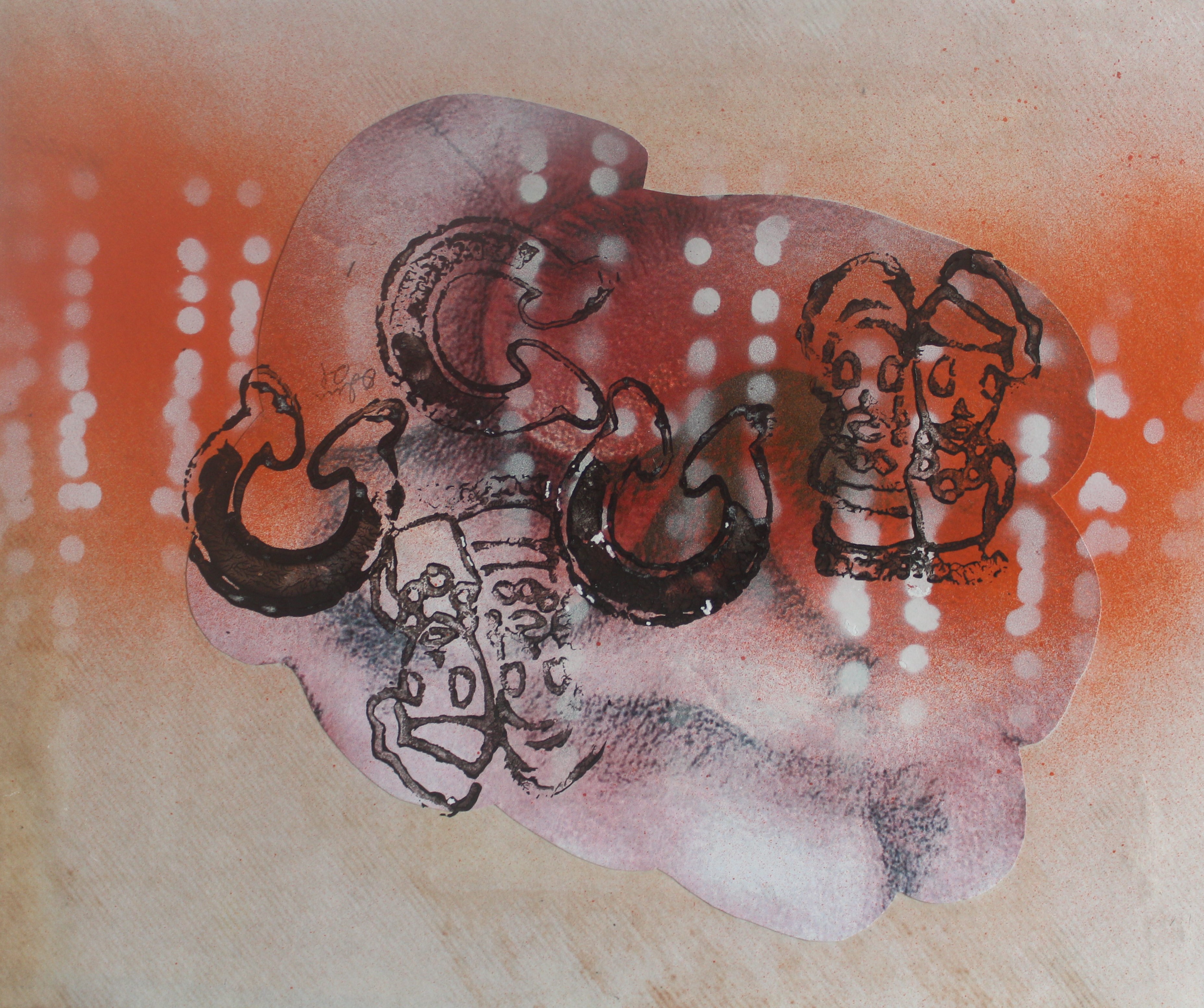

Odun Orimolade’s presentation at Nubuke Foundation explores this simple, mundane question which is central to human life- How do we know the things that we do? The works include drawings, drawing installation, video and performance. Almost every philosopher and worldview has engaged this question one way or the other. Plato suggests that knowledge is innate to a person and is activated through learning. Aristotle, on the other, is an empiricist.

Through perception, introspection, memory, reason and testimony, we are led to the knowledge that we have as humans. Or if we are to decentre our human knowledge, we are led to the knowledge that non-humans have of us.

Growing up, Orimolade’s father read Yoruba literature to her from authors such as Daniel Fagunwa. In a bid to help her understand the language, she picked up the phonetics and tossed them into her mind - a dark space, a generative space. In that space, the words generated images - multiverses of colours and shapes- and fl ed on the wings of her

imagination. It is an encounter that has shaped her experience of knowing.

There is no empty space, if I could start there. There is nothing that is nothing... there’s no void nor emptiness anywhere.

Now as an adult, she expresses her theories of knowing with continuing interest in literature. She points to Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s 2014 novel Kintu. In the novel, Kintu Kidda, a patriarch, out of anger strikes his adopted son dead after finding the son drunk from his beloved gourd . The patriarch is not able to tell the son’s father the truth.

Odun Orimolade’s presentation at Nubuke Foundation explores this simple, mundane question which is central to human life- How do we know the things that we do? The works include drawings, drawing installation, video and performance. Almost every philosopher and worldview has engaged this question one way or the other. Plato suggests that knowledge is innate to a person and is activated through learning. Aristotle, on the other, is an empiricist.

Through perception, introspection, memory, reason and testimony, we are led to the knowledge that we have as humans. Or if we are to decentre our human knowledge, we are led to the knowledge that non-humans have of us.

Growing up, Orimolade’s father read Yoruba literature to her from authors such as Daniel Fagunwa. In a bid to help her understand the language, she picked up the phonetics and tossed them into her mind - a dark space, a generative space. In that space, the words generated images - multiverses of colours and shapes- and fl ed on the wings of her

imagination. It is an encounter that has shaped her experience of knowing.

There is no empty space, if I could start there. There is nothing that is nothing... there’s no void nor emptiness anywhere.

Now as an adult, she expresses her theories of knowing with continuing interest in literature. She points to Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s 2014 novel Kintu. In the novel, Kintu Kidda, a patriarch, out of anger strikes his adopted son dead after finding the son drunk from his beloved gourd . The patriarch is not able to tell the son’s father the truth.

Out of desperation, the father places a curse on Kintu the patriarch. As the novel unfolds, we see the curse manifest in different ways across different generations.

It is a view that is shared in Yoruba philosophy. In Yoruba the metaphysical concept of the transmigration of the soul means that an individual is a representative of a chain of individuals who have previously existed in this world. It is through this window that we acquire an innate knowledge, just by our being as humans and carrying a socio-cultural

DNA. Comparatively, this discussion could be situated in Platonian and ancient Greece debate. This supports the fact that similar intellectual ideas have been well, explored, and cultivated in different societies both in Africa and beyond.

In furtherance, when the healer Damfo was asked a question about his work in Ayi Kwei Armah’s fifth novel The Healers, he responds: I am saying this is seed time, far from harvest time.

It is an indication that his work is not done. In the future, there will be a generation who will continue his work and whose works will know the progenitor’s. This is agreeable with Ewe mythology of creation where the creator Mawu-Lisa recycles the same clay in creating relatives. So when Orimolade goes into the dark space and creates a

multiverse, she delves into a generational pool of thoughts, of those that she is both aware and unaware of. This leads us back to Yoruba philosophy and the roles of Ifa, Ootọ́, Ìgbàgbọ́ and others in opening ourselves to what is there. What to see. What to find. What to be. And how we know what we know.

Another theme that Orimolade points to in the discussion of her works is the idea of differential knowledge. She points to passages in Amos Tutuola’s 1952 novel The Palm-Wine Drinkard, one of the early African novels. One of the

passages reads: As a matter of fact my heart told me to choose the silverish-ghost who stood at the extreme right and if to say I would choose by mouth I would choose only the copperish-ghost ...

In psychology, we read of somatization the idea that psychological concerns could turn into physical, clinical signs of illness like headaches. If through the body-mind connection different body parts could cooperate and act on a stimulus, we can at least imagine that there could be times that the body would disagree.

When we step into Orimolade’s interlocutory world of drawings, our attention is drawn to the fact that we should not discount a mode of knowing because it is beyond our own limitations. For example, Tutuola the novelist once wrote to his publisher that he could photograph ghosts. Around the time that he started his writing, he took to photography.

It is a view that is shared in Yoruba philosophy. In Yoruba the metaphysical concept of the transmigration of the soul means that an individual is a representative of a chain of individuals who have previously existed in this world. It is through this window that we acquire an innate knowledge, just by our being as humans and carrying a socio-cultural

DNA. Comparatively, this discussion could be situated in Platonian and ancient Greece debate. This supports the fact that similar intellectual ideas have been well, explored, and cultivated in different societies both in Africa and beyond.

In furtherance, when the healer Damfo was asked a question about his work in Ayi Kwei Armah’s fifth novel The Healers, he responds: I am saying this is seed time, far from harvest time.

It is an indication that his work is not done. In the future, there will be a generation who will continue his work and whose works will know the progenitor’s. This is agreeable with Ewe mythology of creation where the creator Mawu-Lisa recycles the same clay in creating relatives. So when Orimolade goes into the dark space and creates a

multiverse, she delves into a generational pool of thoughts, of those that she is both aware and unaware of. This leads us back to Yoruba philosophy and the roles of Ifa, Ootọ́, Ìgbàgbọ́ and others in opening ourselves to what is there. What to see. What to find. What to be. And how we know what we know.

Another theme that Orimolade points to in the discussion of her works is the idea of differential knowledge. She points to passages in Amos Tutuola’s 1952 novel The Palm-Wine Drinkard, one of the early African novels. One of the

passages reads: As a matter of fact my heart told me to choose the silverish-ghost who stood at the extreme right and if to say I would choose by mouth I would choose only the copperish-ghost ...

In psychology, we read of somatization the idea that psychological concerns could turn into physical, clinical signs of illness like headaches. If through the body-mind connection different body parts could cooperate and act on a stimulus, we can at least imagine that there could be times that the body would disagree.

When we step into Orimolade’s interlocutory world of drawings, our attention is drawn to the fact that we should not discount a mode of knowing because it is beyond our own limitations. For example, Tutuola the novelist once wrote to his publisher that he could photograph ghosts. Around the time that he started his writing, he took to photography.